Web spies are getting stealthier and stealthier. Recently they've

been caught peering into our browser histories to determine the sites

we've visited, even in so-called privacy mode with cookies disabled, as

Dan Goodin described earlier this month on

The Register.

Many of the companies whose sites were discovered using the technique

claimed to have had no idea and immediately decried the spying. Julia

Angwin reported on many of these surprise responses on the Wall Street

Journal's

Technology site.

If the owners of the spying sites aren't even aware of the activity,

what are unsuspecting visitors to do? Well, you could wait for the

government to take action, as CNET's Declan McCullogh reports in the

Privacy Inc. blog.

Or you could rely on the online advertising industry to police itself,

despite the marketers' inability to determine which spying practices

violate their own guidelines, which Julia Angwin describes on the WSJ's

Digits blog.

Personally, I'd rather take matters into my own hands. Here are five

ways to reduce the chances that your browsing habits are being recorded.

Block ads and super-cookies before they can download

Last May, Microsoft and Adobe announced that deleting cookies in

Internet Explorer 8

and 9 would also delete the long-lasting Flash cookies, or local shared

objects (LSOs). The long-awaited change requires Flash 10.3 or later,

as Microsoft's Andy Ziegler explains on the

IEBlog.

Add-ons for Mozilla

Firefox

and Google Chrome go a step further by allowing you to prevent LSOs and

other tracking files from being downloaded along with a Web page's

content. I first wrote about Giorgio Maone's free

NoScript add-on for Firefox in a

post from January 2008.

The extension lets you block Flash and Javascript on a site-by-site and

source-by-source basis. I can't think of a reason why Firefox users

would

not use this add-on.

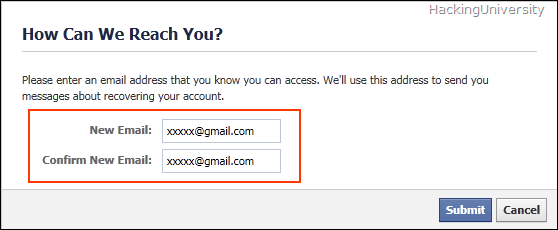

NettiCat's free

BetterPrivacy

extension for Firefox lets you decide which Flash cookies to allow and

delete. The program can be set to notify you whenever a new LSO is

stored, delete the default Flash Player cookie, and even set a keyboard

shortcut for erasing LSOs. By default, BetterPrivacy removes all Flash

cookies when you close Firefox.

The free BetterPrivacy add-on for Firefox automatically deletes Flash cookies when the browser closes.

(Credit:

screenshot by Dennis O'Reilly)

Another great Web-privacy tool that's available for both

Firefox and Google Chrome is AdBlock Plus, which not only removes ads

from sites but also lets you customize its 40-plus filter subscriptions

for ads and known malware domains. Developer Wladimir Palant suggests a

$5 contribution. The version for Firefox is available on the

Mozilla add-ons site, and the one for Chrome can be downloaded from

Chrome Web store.

Improve security and browsing speed in one fell swoop

If OpenDNS isn't the worst-kept secret on the Web, it should be. The

service replaces your existing Domain Name System service with one

that's both faster and safer. The ad-supported

OpenDNS Basic for home users can be upgraded to the ad-free

OpenDNS VIP ($10 per year). There's a

version of K-12 schools and

one for organizations.

OpenDNS works by using a network of Web-cache servers that put site

content closer to your browser to minimize the number of hops required

to deliver the data. The servers also filter dangerous or inappropriate

content based on the criteria you select. For more on the service, see

this post from May 2010 (scroll to "Filter potentially dangerous sites").

Set your browser to clear your history, cache, and cookies on exit

There are good reasons to retain your browser history, cache, and

first-person cookies. Holding onto your history makes it easier to

retrace your online activities. A big browser cache allows pages you

revisit to load faster. And cookies allow sites to make suggestions

based on what they already know about you.

Personally, I'd rather

bookmark pages I expect to return to; I don't mind pages I revisit

loading more slowly; and I don't care for sites' personalized

recommendations. Where I've been and what I do on the Web is nobody's

business but mine...and Google's, of course. And my ISP's, and the

National Security Agency's... . But you gotta draw the line somewhere.

To set Firefox not to save your browsing history, click Tools >

Options > Privacy. (If the standard menu isn't visible, press Alt.)

You can either select "Never remember history" in the "Firefox will"

drop-down menu, or "Use custom settings for history" to view more

options. Check "Clear history when Firefox closes" to activate the

Settings button.

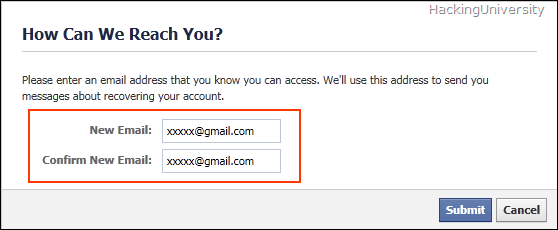

To view more options for clearing your browsing

history in Firefox, check "Clear history when Firefox closes" and click

the Settings button.

(Credit:

screenshot by Dennis O'Reilly)

Click Settings to open a dialog that lets you clear specific

types of data when Firefox closes. These include browsing, download, and

form and search history, as well as cookies, log-in IDs, the browser

cache, passwords, and site preferences.

Firefox's options for clearing data when the

browser closes include browsing and download history, forms and search

history, cookies, cache, logins, and passwords.

(Credit:

screenshot by Dennis O'Reilly)

You can also set Firefox to remain in Private Browsing mode,

to tell sites you don't want to be tracked, and to never remember

history. On the Security tab of the Firefox Options dialog you can

uncheck "Remember passwords for sites."

To set Google Chrome to

clear data on exit, click the wrench icon in the top-right corner,

choose Options > Under the Hood > Content Settings, and check

"Clear cookies and other site and plug-in data when I close my browser."

To view the personal data the browser is storing, click "All cookies

and site data."

Google Chrome's option for clearing cookies and

cache on exit are located in the Content Settings dialog in the Privacy

section Under the Hood.

(Credit:

screenshot by Dennis O'Reilly)

In Internet Explorer, click the gear icon in the top-right

corner (or Tools on the standard menu) and choose Internet options >

General. Check "Delete browsing history on exit" to remove cookies,

cache, saved passwords, and Web-form data automatically when the browser

closes.

Internet Explorer's option for deleting your browser history on exit is on the General tab of the Internet Options dialog.

(Credit:

screenshot by Dennis O'Reilly)

To view more options, click the Delete button. By default,

the option to keep cookies and temporary files for your favorite sites

is checked, as are the options to delete temporary Internet files,

cookies, and history. Unchecked by default are the options to delete

your download history, form data, passwords, and "ActiveX Filtering and

Tracking Protection data."

Sign out whenever you're done using a Web service

It's convenient to remain signed into Gmail, Facebook, and other Web

services you're likely to return to frequently in the course of a

computer session. You may also be tempted to use your Facebook sign-in

ID on sites that partner with the company. Unfortunately, the services

may be sharing your personal data a bit too freely.

Of course, some people find Google's recording of their Web activities helpful. (In a

post from July 2009,

I described how to manage what Google knows about you.) But if you'd

rather not share your browsing habits, the simple solution is to sign

out when you're not actively using the service.

Send and receive from Webmail accounts via a desktop e-mail program

A comment to a recent post relating to Microsoft Outlook and

Thunderbird asked why anyone would use a desktop mail program outside of

work. Just a few days earlier a friend complained that Gmail lacked

several features he had come to rely on in Outlook. I suggested he

forward his Gmail messages to his IMAP or POP3 account, as I described

in a

post from December 2007.

(I've also described in previous posts how to

merge your Outlook and Gmail contacts, how to

combine and organize your e-mail accounts, and how to

sync contacts and calendars between Outlook, Gmail, and iPhone.)

The Electronic Privacy Information Center (EPIC) claims that Gmail

violates the privacy of non-subscribers by extracting information from

the mail they send to Gmail addresses. EPIC also finds Gmail's

data-retention policy and profiling practices a threat to privacy. (See

EPIC's Gmail FAQ for more details.)

When you forward mail from a Webmail service to a desktop mail client,

the contents of the messages you receive are still scanned by Google's

bots before the mail is forwarded, but at least you can reply to the

messages from your ISP mail account.

Many people claim the fuss

about Gmail privacy is overblown. You can enable HTTPS for all your

Gmail transmissions, as I described in a

post from August 2008.

But for individuals and organizations sending and receiving

confidential or otherwise-sensitive data, IMAP and POP3 mail systems are

generally more secure than Webmail services.